Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (or NAFLD, which in English translates to “ non-alcoholic fatty liver disease ”) is a pathophysiologic condition evidenced by a clinical diagnosis that includes the presence of 5% or more fatty liver disease as determined by liver imaging or biopsy in the absence of secondary causes of accumulation of liver fat. This means that, under normal conditions, the presence of accumulation of fat inside the liver cells is considered physiological, but when this exceeds 5% a pathological condition begins to take shape .

One of the main reasons is linked to the significant increase in energy introduced with food , mainly carbohydrates and fats, which is followed by an increase in fatty acids which accumulate inside the liver cell, in essence it is the onset of the same metabolic mechanism that leads to obesity and diabetes. Steatosis in itself is not a big problem, but what is most worrying is the fact that it presents itself as the beginning of a process capable of evolving into steatohepatitis (NASH), characterized by an increase in the accumulation of fatty acids in the hepatocytes with the formation of inflammation and fibrosis, which is followed, in the process of evolution of the disease, by cirrhosis of the liver , a very serious pathological condition.

Obesity is a common feature of many metabolic diseases, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Obesity was rare in ancient times, often lauded and confined to the aristocracy. However, on occasion it was noted that excess body weight could lead to health problems. Hippocrates, in 400 BC, was one of the first to comment on the dangers of obesity:

"It is injurious to health to take in more food than the constitution can bear, when at the same time one does not exercise to carry off this excess..." ( Translated from Hippocrates, circa 400 BC).

Several famous doctors have cataloged the ill health associated with obesity. Pathologist GB Morgagni was the first to describe ectopic fat from sectioned post-mortem studies and to associate it with the development of atherosclerosis. William Osler listed ectopic fat as a causative factor in angina pectoris. By the early nineteenth century much of the modern understanding of ectopic fat within key organs was being delineated. Although Hippocrates recognized exercise as a mitigating factor against obesity, Ludovico Nonnius was one of the first physicians to embrace diet as an important factor in health, therefore, the basis for the implications of.

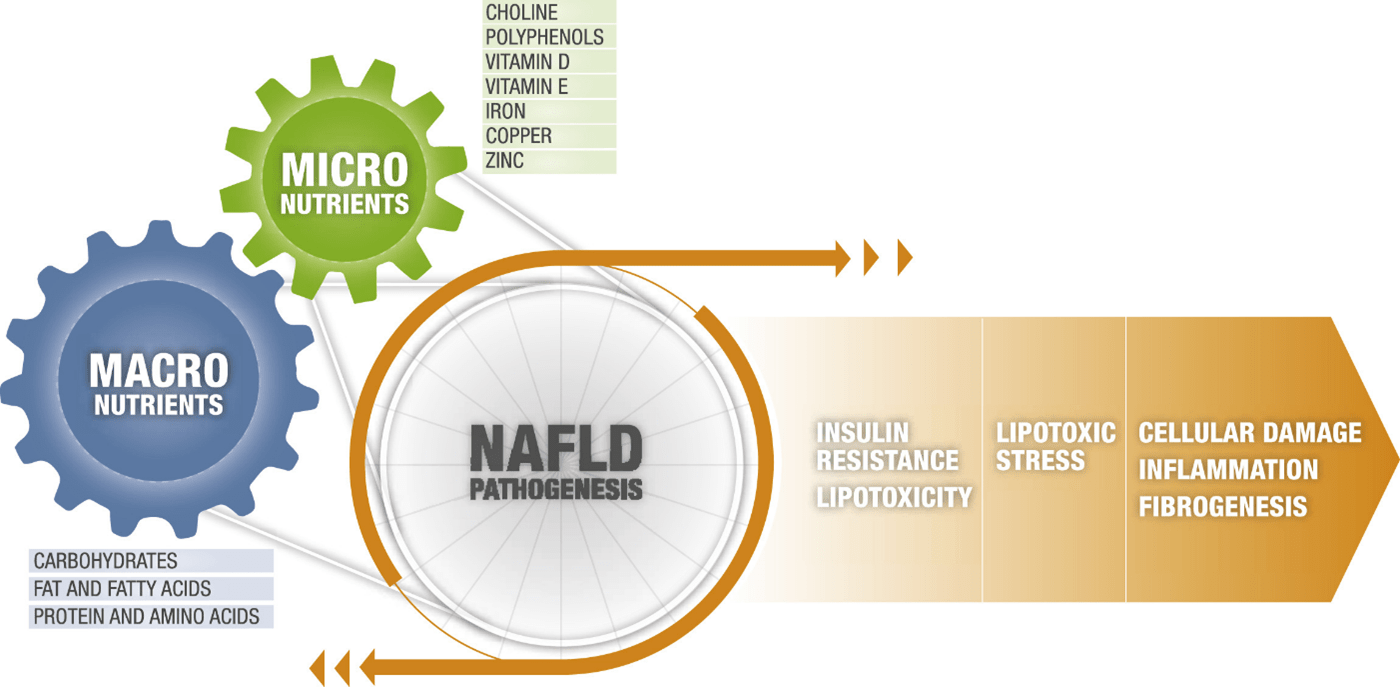

Healthy eating habits, weight loss, and increased physical activity (PA) are the cornerstones of managing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), but it needs to be emphasized that the diet of humans typically contains thousands of bioactive molecules that orchestrate a variety of metabolic and signaling processes in health and disease, encompassing a natural combination approach. Although the composition of foods varies widely, there is substantial cumulative evidence suggesting that specific dietary macronutrients and micronutrients can influence the biological processes involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and therefore it is incorrect to speak only of the energy component of food and therefore of the energy balance.

In general, the disease appears to progress from fat accumulation (i.e., steatosis or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFL]) to inflammation (i.e., non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH]) to fibrosis and finally cirrhosis, crossing over two main principles, Critical nodes of NAFLD pathogenesis, emerging in the context of metabolic substrate overload:

- Node of constitution of the disease: insulin resistance and lipotoxicity

- Disease Progression Node: Lipotoxic fatty acids (FA) lead to cell damage, inflammation, and fibrogenesis

Macronutrients and micronutrients in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Nutrients significantly influence pathological outcomes in several chronic diseases. Polyphenols, carotenoids, flavonoids and terpenoids are known to regulate inflammation, proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis . Diet and lifestyle modifications have been shown to prevent 30% to 40% of all cancers , therefore, the ways in which specific dietary constituents influence biological processes to influence health outcomes are an area of investigation active.

In particular:

Epidemiological studies show a strong association between a large increase in fructose consumption and the incidence of NAFLD particularly when fructose intake exceeds 25% of energy requirements. Conversely, carbohydrates partially or completely resistant to digestion are associated with a reduced risk of pathogenesis. Importantly, fermentable polysaccharides such as inulin or pectin are metabolized by the gut microbiota to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which not only improve insulin resistance but activate metabolic pathways capable of inducing epigenetic and anti-inflammatory effects to modulate metabolic disease status.

Dietary FAs may modulate the activity of key cell types (eg, hepatocytes, macrophages, hepatic stellate cells) implicated across the NAFLD spectrum, thus, dietary fatty acids may facilitate development, prevention or the reversal of some characteristics of NAFLD depending on fatty acid composition, carbon chain length and molecular targets involving: Excessive intake of long-chain saturated FAs found in foods such as animal products promotes oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation; in contrast, monounsaturated dietary fatty acids (MUFA; for example, oleic acid) and polyunsaturated (for example, linoleic acid [n-6], alpha-linolenic acid [n-3] and arachidonic acid),

Although attention has largely been focused on carbohydrates and fats with respect to their roles in the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, Protein have received less attention. This omission is now starting to change, and a growing body of data suggests that a high protein intake could help reduce levels of fat in the liver , whether the protein came from animal or plant sources and independent of variations in body weight; However, it should not be forgotten that an excess of protein has also been linked to insulin resistance: these results underline theThere is the importance of balancing the quantity and quality of dietary protein versus other nutrients as a key determinant of metabolic health .

Certain amino acids in the diet may preferentially modulate key biological processes:

- Leucine, isoleucine, and valine (together referred to as branched-chain amino acids [BCAAs]) regulate several important hepatic metabolic signaling pathways, including insulin signaling, glucose regulation, and efficient channeling of carbon substrates for oxidation through the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Impaired BCAA-mediated upregulation of the TCA cycle is thought to be a fundamental defect driving mitochondrial dysfunction in NAFLD.

- Glutamine, serine, and glycine levels , which collectively influence glutathione synthesis, inflammation, and oxidative stress pathways, are also impaired in NAFLD. e.g. serine deficiency, observed in patients with NASH, directly affects cellular levels of acylcarnitine, evidence of impaired mitochondrial function and, consequently, reduced fuel consumption by FAs leading to mitochondrial fragmentation.

- Lower glycine levels were significantly associated with an increasing number of metabolic syndrome components in a cross-sectional investigation.

- Dietary arginine and citrulline appear to affect the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier, a process increasingly recognized as a key pathogenetic feature of NASH progression.

Micronutrients and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Choline is metabolized largely in the liver to phosphatidylcholine and plays an important role in lipoprotein assembly and secretion, and in host-gut microbiota interactions .

- polyphenols (such as resveratrol, curcumin, quercetin and green tea catechins, commonly found in foods such as fruits, vegetables, wine and coffee) reduce IHTG (intra hepatic triglycerides) through several mechanisms, including inhibition of lipogenesis through downregulation of SREBP1c and inducing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

- Recent epidemiological evidence shows that patients with NAFLD are more frequently deficient in vitamin D than the general population and circulating vitamin D levels are proportional to the degree of fibrotic evolution.

- In addition to being one of the most powerful antioxidants in nature, vitamin E is considered the main fat-soluble antioxidant involved in the regulation of gene expression, inflammatory responses and the modulation of cell signaling. Sources of vitamin E are similar to those of polyunsaturated fatty acids and include olive oil, nuts and green vegetables; therefore, vitamin E deficiency is also likely to be seen in the typical Western diet.

- Copper, Iron and Zinc: Although it is an essential nutrient in multiple cellular processes and erythropoiesis, excess iron is commonly observed in patients with NAFLD and is associated with organ dysfunction secondary to reactive oxygen species formation. Copper deficiency is observed in human NAFLD and is associated with insulin resistance, steatosis, and accelerated progression of NASH. Furthermore, dietary copper deficiency and fructose excess synergistically exacerbate liver injury and accelerate hepatic fat accumulation, inflammation, and fibrogenesis. The association between liver disease and zinc deficiency has been recognized for more than half a century. Zinc deficiency initiates insulin resistance, iron overload, and fatty liver disease, which follows impairment of

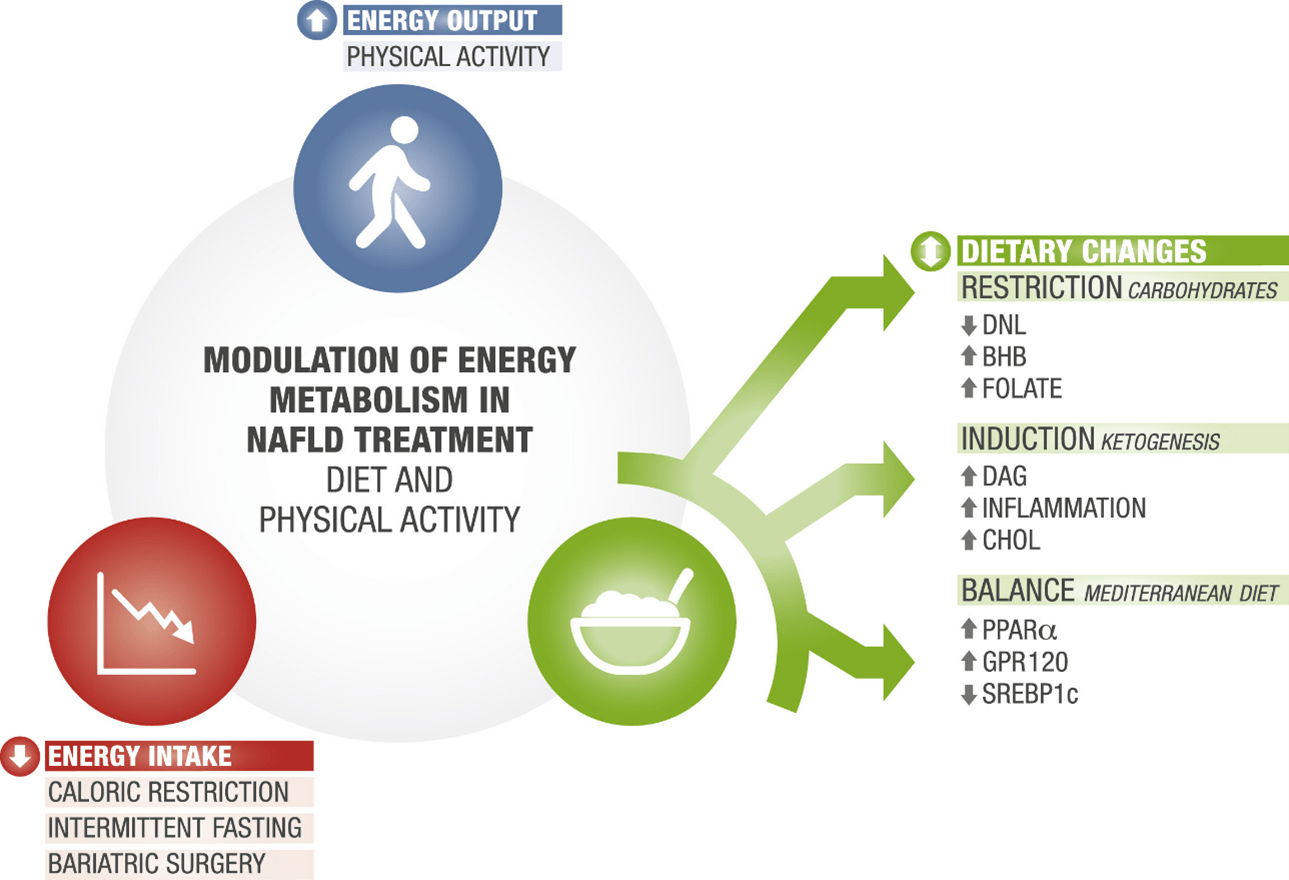

Modulation of metabolism: interventions for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with diet and physical activity

- Carbohydrate restriction

- Induction of ketogenesis

- Composition of balanced diet

- Metabolic modulation by decreasing energy intake

- Metabolic modulation by increasing energy production

Dietary recommendations for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease based on currently available evidence

- Prioritize intact starches like whole grains, and limit or avoid refined starches like white bread and white rice;

- Replace some of the carbohydrates, especially refined carbohydrates, in your diet with additional protein from a blend of animal or plant sources, including chicken, fish, cheese, tofu, and legumes;

- Include a variety of bioactive compounds in your diet by consuming fruits, vegetables, coffee, tea, nuts, seeds and extra virgin olive oil;

- Get most of your fats from unsaturated sources, such as olive oil (ideally extra virgin), canola oil, sunflower oil, safflower oil, canola oil, or nuts and seeds;

- Limit or avoid added sugars, whether they are sucrose, fructose, maltose, maltodextrin or syrups. If any of these words appear in the first 3-5 ingredients of a food, it's best to avoid that item and choose a sugar-free version instead. Examples are commercial yogurts and cereals;

- In particular, avoid sugar in dissolved form such as sugary fizzy drinks/soft drinks, lemonade, fruit juices, smoothies, and sugar added to tea and coffee.

Carmine Orlandi

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Impact of Dietary Patterns and Nutrition in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

Kim A, Krishnan A, Hamilton JP, Woreta TA.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021 Mar;50(1):217-241.

Nutrition and physical activity in NAFLD: an overview of the epidemiological evidence.

Zelber-Sagi S , Ratziu V , Oren R .

World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Aug 7;17(29):3377-89.

Nutrition and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Current Perspectives.

Chakravarthy MV, Waddell T, Banerjee R, Guess N.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020 Mar;49(1):63-94.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Pathophysiology and Management.

Carr RM, Oranu A, Khungar V.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2016 Dec;45(4):639-652